NGV

42

Table concept and installation, exhibited at The National Gallery of Victorias ‘Art of Dining’.

Concept

Furniture Design

Installation

A TABLE, NOT A STAGE

Dining is loaded with layers of context. To dine is to participate in a universal act which is both intimate and instinctual. Communal dining goes further, engaging a complex performance of ritualism involving community, social story and audience. To ponder dining as Art, may give cause to transform the act of dining into a form of collective exhibitionism, centred around the table. In this reading, the table becomes an object with its own choreographed conditions and exaggerated sense of theatricality. Participation is implied, but is it meaningful? In a context where the dominant gestures are theatrical, how can a table pose a different question: Where is the art in dining?One possible answer, to host and be hosted. Not to perform hospitality but truly enact it. To build a spatial condition that centres conversation, participation and mutual presence.

The Art of Dining exhibit unfolds as a theatre of surfaces beneath the iconic Leonard French stained-glass ceiling of the National Gallery of Victoria’s vaulted Great Hall. Tables, authored by artists, architects, and designers, often push toward spectacle. Lush, layered, ornamental constructions that stake their presence in volume and audacity. A room calibrated for performance and display. Where function recedes behind concept. And the table becomes not a place to gather, but an object to behold. In a space geared towards spectacle, encouraging us to shout and gesticulate, quiet introspection becomes the boldest approach.

Created in collaboration with interior architect Pip McCully of Studio Wonder, the submission is anchored in an approach that privileges function before form. Allowing purpose to shape aesthetics rather than the inverse. Not designed to dazzle but to serve. Not to declare, but to invite. An exploration of reduction as an attempt to curate a receptive condition. Inverting bombast and decoration, it collapses the standard centrepiece, or epergne, to carve out a centring force. It is a table conceived not as a stage or object of reverence, but as a structure for participation and a tool for connection.

A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction by Christopher Alexander, Sara Ishikawa, and Murray Silverstein, with contributions by Max Jacobson, Ingrid Fiksdahl-King, and Shlomo Angel. 1977, Oxford University Press.

A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction by Christopher Alexander, Sara Ishikawa, and Murray Silverstein, with contributions by Max Jacobson, Ingrid Fiksdahl-King, and Shlomo Angel. 1977, Oxford University Press.

A SEAT AT THE SCULPTURE

Drawing from the canon of Donald Judd and Isamu Noguchi, the object explores the sculptural qualities of the table. An item with conceptual and ideological underpinnings, extending well beyond its role as a functional piece of furniture. However, it is not so much an artwork as it is an intervention: a response to the scale and geometry of the space, the social function of dining, and the human needs embedded in the act of gathering. Both Judd’s refusal of ornament in favour of clarity and Noguchi’s understanding of sculpture as landscape proffer rich frameworks through which design can support rather than dominate a dining experience.

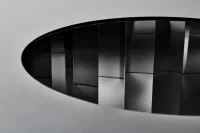

The result, a functional sculpture that resists ornamentality without rejecting beauty or intrigue. Its form follows its function. But its function is deeply human. Surfaces reflect and refract the stained-glass ceiling above, creating a quiet dialogue with the architecture of the space. Geometry encourages eye contact. Proportions facilitate exchange. The table acts as a social tool, amplifying interaction rather than absorbing attention. It is sculpture that holds space. Sculpture that is inhabitable.

Echoing Lee Mingwei’s The Dining Project, in which artist and guest share a meal in a gallery after hours, the table becomes a site of intimate exchange. A ritual act within an institutional setting. Here too, intimacy is structured through design. Not forced but enabled. The act of eating together is no longer backgrounded by spectacle but framed as the spectacle itself. In doing so, the submission reclaims hospitality from performance. And restores it to its most essential gesture: the invitation to connect.

Still from Chefs Table, Season Two, Episode 6. Gaggan Anand, 2015.

Still from Chefs Table, Season Two, Episode 6. Gaggan Anand, 2015.

PATTERN LANGUAGE

Dining places us within space and within rituals that are dictated by such spaces. It makes us aware of the ways in which space arranges behaviour. How proximity fosters exchange. And how design can support (or obstruct) participation. Like Chris Burden’s Exposing the Foundation of the Museum (1986), which physically unearths the institutional skeleton beneath the gallery floor, this table exposes the soft infrastructure of communal experience. It asks: What is being constructed here, beyond the visual? What are we sitting within, and what are we sitting for?

This line of inquiry draws further resonance from A Pattern Language, the seminal work on architectural behaviour by Christopher Alexander and colleagues, which emphasises patterns of human interaction as a blueprint for spatial design. In that spirit, the table functions not as an aesthetic object but as a tool for enabling specific behaviours—facing, sharing, leaning in, listening. A kind of invisible choreography embedded in blackened stainless steel.

SWISS ARMY KNIFE FUNCTIONALITY

This notion of the table as a tool, and surface as malleable material to be shaped and weathered, conjures in the imagination a chef’s table in an Italian kitchen. Not the exclusive, voyeuristic kind, but a real communal, working table. Where the act of cooking merges with the act of serving. And where the social rituals of dining are grounded in presence and participation. An active vs passive experience. It also embraces multiplicity, a kind of Swiss-army knife functionality. The table as a kitchen top, a conversation pit, a shared bench. A site not for looking at, but for being with, in so many ways.

Design, at its most resonant, does not just shape objects. It shapes encounters and our relationship with the world around us. This is a table built for that purpose. Not to impress from a distance, but to support from within. It asks less of the eye, and more of the body. Less of the viewer, and more of the guest. It seeks to elevate the most simple and universal of rituals into an experience which embodies the core of our needs and desires; to gather, connect, share and savour.

Photography: NGV Photography. Leonard French’s stained glass ceiling inside the Great Hall at NGV International.

Photography: NGV Photography. Leonard French’s stained glass ceiling inside the Great Hall at NGV International.

Photography: NGV Photography. Leonard French’s stained glass ceiling inside the Great Hall at NGV International.

Photography: NGV Photography. Leonard French’s stained glass ceiling inside the Great Hall at NGV International.

Collaborator: Pip McCully, Studio Wonder. Photography: Daniel Hermann-Zoll. NGV Photography: Leonard French’s stained glass ceiling inside the Great Hall at NGV International.

A conversation between Pip McCully (PM) from Studio Wonder, Rhys Gorgol (RG) from The Company You Keep and Matt Leach (ML) from Australian Design Radio.

ML

We’re talking about the table installation you created in collaboration. This was for NGV — the National Gallery of Victoria — Art of Dining series, 2019. I’m interested, Rhys — what attracted you to this project, because it’s not your typical design project, is it?

RG

It is not, we’re not dealing with pixels and InDesign here. The starting point was the collaboration — being able to create something outside of a commercial brief with a respected peer. Pip and I have a pretty long relationship. We used to share a studio space together. When Pip showed me the previous events, the kind of work there and what we were asked to do, it seemed like something that could provide a very interesting result when you combine an interior practice and a graphic practice coming together.

ML

Pip, talk to me more about the concept of the table. Because upon first appearance, it seems very much more restrained than some of the other ones I’ve seen on the NGV Instagram.

PM

Most of the participants are interior stylists or interior designers, and so it was quite a unique scenario to be asked in the first place. Especially as we don’t do a lot of styling work — much more functional design and architecture. So when we started to look at the design, it was key to collaborate with Rhys, in terms of potentially approaching the designers, and it’s a version of art direction as opposed to just styling and decoration. So the concept then became much about breaking down what it means to dine, and then how we can produce the most pared-back restrained design response to that. To actually design an experience within the space, as opposed to an ornamental addition to the Great Hall.

00:00 / 00:00

ML

I’m interested in that, “pared-back”. Rhys — I read a quote by you that talks about stripping back to the elemental. Is that a design philosophy for your studios?

RG

It’s definitely something that underwrites our approach to design. Design is there to serve a function or for a purpose, and there’s a clarity that comes with economy. So when you don’t shroud an idea or a purpose with external things, or things that are potentially superfluous, then they avoid distracting from the intention of what you’re trying to set out.

ML

I want to talk about that intention a little bit more. Looking at other examples, there was very much this idea of going up and obscuring the view across the table, where your centrepiece seemed to be sunken down. Rhys, how did that come about, what was the idea behind that?

RG

It’s twofold. The approach and the collaboration really followed a conceptual practice rather than an ornamental practice. With the brief being Art of Dining, you start sitting and thinking about what actually constitutes dining. Is dining just the object that you sit on or sit around? Is it the food that you eat, is it the people that you’re sitting with, is it the conversation? It’s all those things and so in creating something, we wanted to create a platform that fostered and elevated that notion of dining. Which is, as I mentioned, all of these kinds of things. So the first thing was to remove any obstruction. If you’ve got something in the centre of the table and you can’t see the eyes of the person across the table, then you’re hindering that conversation about food or service or whatever it happens to be. There’s a practical component to restraining and pulling it down. But also as soon as you start to do that, it starts to be reminiscent of other things — such as a hearth or even a fire around a camping place, which is more community-driven and more fundamental to the desire of people coming together and breaking bread together.

ML

You mentioned the idea of hearth. I’ve seen some images where you’ve got candles in there and it creates almost this fire that everyone is sitting around.

PM

It’s exactly the point. It’s about bringing in intimacy so that we could actually have people sit at the table, be connected to each other, but also there’s an intimate connection to the table by looking down and into the central space. The design was quite key in that it’s a circle, but we designed a mirrored, faceted interior to that central hearth. So that no matter what was positioned or placed within that point, you could get a particular aspect from where you sat at any point of the diameter of the circle.

RG

It became something interesting to us. If you elevate the value of the experience and you remove the power of the object and the physicality of the object, then you start to think about how you can mark that experience. With the candles there’s a kinaesthetic component to it, there’s a movement. And so it is literally passing time and signifying that which is interesting. And there’s these things that are subconsciously happening when people gather around campfires that we don’t really stop and think about. But when you interject them into the hearth or the central component of the table, that humanity, that warmth of that experience, or the connection of breaking bread around this central object, is really brought back.

ML

I love the idea that you got the brief, it was a brief for a table and the first thing you did was work out how you could get rid of the table.

PM

Exactly. How can we design a dining experience?

RG

It’s interesting — in terms of how it sat in context with the other entries or the exhibition as a whole, in that room the general response was grand. There were large gestures and our installation is deliberately restrained because it’s about the sense of intimacy, it’s about the people that are sitting around it. So when that sits in the context of the Great Hall, which is these huge lofting ceilings surrounded by these very loud, grand gestures, it becomes a juxtaposition that then draws people over to it. Because at the start they almost think there’s something wrong. But then as they draw closer they start to understand and reveal it, which means they need to engage with it in a bit more of an intentional way. They can’t just walk around with their periphery and think “I understand this, I understand that”, they have to come over and engage, and that was something that was a really beautiful response to the output.

ML

One of the things to also mention is that a lot of people may not understand the context of where this table is being placed. It’s going in the NGV Great Hall, which has this most amazing stained-glass ceiling across the top. Talk to me more about that Pip, because it’s obviously part of your thinking?

PM

That was key to our thinking. The opportunity to design an object to be placed into that space is super important, so how do we then not then compete with the context? The way we wanted to approach the design was to insert something that only functioned for the purpose of what it was required, but also was highly sympathetic to the context of the space. And in terms of decoration, what more do you need than Leonard French’s stained-glass ceiling in that cavernous beautiful hall, and so why would we need to add anything more to that space, and instead, how can we enhance that? So the highly polished stainless steel surface was key to reflecting that. From wherever you stood you could see that’s what the decoration became, the overlay through that space.

RG

It’s important, the idea of context, not only in terms of people around the table or food on the table, but where that table sits. And the Great Hall in the NGV on St Kilda Road is an epic space, and that stained-glass ceiling is extremely iconic. So if someone has the opportunity to dine in that space, you really want to talk to the cues of that environment that are extremely unique — that heighten or enrich the experience of someone sitting around a table breaking bread.